SDI Data Policies

Legal frameworks on SDIs, open data, data ecosystems and arrangements for sharing

WELCOME!

The following modules give an overview of the non-technical aspects related to Spatial Data Infrastructures (SDI). This training material aims to guide and improve skills of SDI owners and managers.

This course material has been developed using tools, concepts and guidelines under the framework of the EO4GEO project. Unless stated otherwise, all rights for figures and additional material are with the author(s).

You can navigate through the course by pressing the navigation arrows at the bottom of each slide or using your arrow keys on your keyboard. You can move horizontally (← →) for viewing each theme and vertically (↑↓) to navigate through its contents.

SDI Data Policies

| 1 | Introduction |

| 2 | Legal framework on SDIs |

| 3 | Open data |

| 4 | Data sharing arrangements |

| 5 | Data ecosystems and data spaces |

Scope of this lecture

- Focus on the access to and sharing of data and information

- Focus on geospatial data and information, but also looking at other – more general – data policies that are relevant to spatial data infrastructures

Learning objectives

- Explain why a legal framework on Spatial Data Infrastructures is important

- Explain the key characteristics and elements of a legal framework on Spatial Data Infrastructures

- Explain the evolution from traditional data sharing arrangement towards open data policies (and associated licenses)

- Explain the link between SDI and other (open) data policies

- Explain recent developments in SDI and broader data policies and associated challenges related to the legal framework

SDI Data Policies

| 1 | Introduction |

| 2 | Legal framework on SDIs |

| 3 | Open data |

| 4 | Data sharing arrangements |

| 5 | Data ecosystems and data spaces |

Legal framework

A good legal framework is vital for the development of a well-functioning Spatial Data Infrastructure (SDI). What constitutes a good legal framework is, however, not easy to define.

For an SDI, the set of laws and regulations can be very wide and diverse, involving rules on data, coordination, standards, funding, etc. Moreover, these rules and regulations can take many different forms:

- legal acts adopted by parliament,

- executive orders or decisions,

- cooperation agreements,

- memoranda of understanding,

- bilateral arrangements etc.

Legal framework

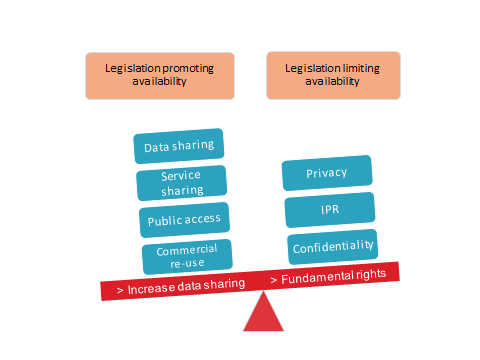

From a data perspective, the legal framework can be distinguished into

- Laws and regulations that promote the availability of spatial data and

- Laws and regulations that make the availability of spatial data depending on conditions.

Underlying these two types of legislation are rules that are more related to the procedural aspects in the relationships between different elements or stakeholders of an SDI

- for example: legislation regarding cooperation (e.g. rules on coordinating structures of procedures for cooperation agreements).

Legal framework

Legal framework

Two important criteria for ‘assessing’ a legal framework are coherence and quality:

Coherence: Do the different rules that are applicable to that SDI complement each other or are there contradictions?

Quality: Does the legal framework underpinning the SDI contribute to reaching the SDI’s key objective of optimised spatial data sharing?

Key objective of a legal framework should be that it formalizes the key principles into a binding framework that provides a minimum set of rights and obligations that are available to everyone and do not depend on personal or situational circumstances

= providing legal certainty and means for responding to problems

Different types of use

‘Sharing’: Public bodies delivering or obtaining information for the purposes of a public task. Sometime involves exchange of data.

‘Public access’: If a person wants to obtain information in order to exercise his/her democratic rights. Usually relating to democratic or political purposes or accountability of government. Purpose is to learn the content.

‘Commercial re-use’: Use of information for commercial purposes outside the public task for which it was collected. Often has an economic goal and involves manipulation or analysis.

Types of use ≠ Types of users

Restricting spatial data availability

Intellectual property rights: to protect the financial interests of the right holders

Legislation protecting the privacy of individuals: provides the means to individuals to limit use of their personal information.

Legislation limiting access to government information for purposes of security.

Liability: guaranteed information quality is likely to have a limited timeframe, and may not apply to all uses (“dataset is not necessarily without error”)

SDI Data Policies

| 1 | Introduction |

| 2 | Legal framework on SDIs |

| 3 | Open data |

| 4 | Data sharing arrangements |

| 5 | Data ecosystems and data spaces |

Open data

- Data that can be freely used, reused and redistributed by anyone

The goals of the open data movement are similar to those of other "Open" movements such as open source, open hardware, open content, and open access

- Why should government data be open?

- Transparency, accountability and participatory governance

- Leverage the potential of government data through the development of applications and services by third parties

- More efficient and effective information provision and service delivery

8 principles of open government data

1. Complete

All public data is made available. Public data is data that is not subject to valid privacy, security or privilege limitations.

2. Primary

Data is as collected at the source, with the highest possible level of granularity, not in aggregate or modified forms.

3. Timely

Data is made available as quickly as necessary to preserve the value of the data.

4. Accessible

Data is available to the widest range of users for the widest range of purposes.

8 principles of open government data

5. Machine processable

Data is reasonably structured to allow automated processing.

6. Non-discriminatory

Data is available to anyone, with no requirement of registration.

7. Non-proprietary

Data is available in a format over which no entity has exclusive control.

8. License-free

Data is not subject to any copyright, patent, trademark or trade secret regulation. Reasonable privacy, security and privilege restrictions may be allowed.

Compliance must be reviewable.

SDI Data Policies

| 1 | Introduction |

| 2 | Legal framework on SDIs |

| 3 | Open data |

| 4 | Data sharing arrangements |

| 5 | Data ecosystems and data spaces |

Data sharing arrangements

- Licensing agreement between two or more organisations concluded prior to the datasets or services being required

- May involve one or multiple data sets or services

- Benefits for providers and users:

- Removal of obstacles at the point of use

- Reduces the efforts of establishing data sharing agreements

- Requires the management of only a small amount of contracts, and, where required, financial transactions

- The more public authorities and data sets can be included in a single arrangement, the more transparent and smooth sharing becomes for the end-users.

- Preparatory negotiations require time and efforts

Framework agreements

- Licenses are mechanisms to give organizations and people the permission to use spatial data sets and services.

- A license is legally binding, and defines the conditions of use of the related spatial data sets and services.

- A license can take many forms: e.g. e-mail, a non-transactional statement on a webpage, a click licence, or a licence agreement signed by all the parties involved.

- Standard licenses: reduced number (for different types of users and different types of use), harmonised terms

- Open licenses: one that grants permission to access, re-use and redistribute a work with few or no restrictions

Licenses

Licenses are mechanisms to give organizations and people the permission to use spatial data sets and services.

A license is legally binding, and defines the conditions of use of the related spatial data sets and services.

A license can take many forms: e.g. e-mail, a non-transactional statement on a webpage, a click licence, or a licence agreement signed by all the parties involved.

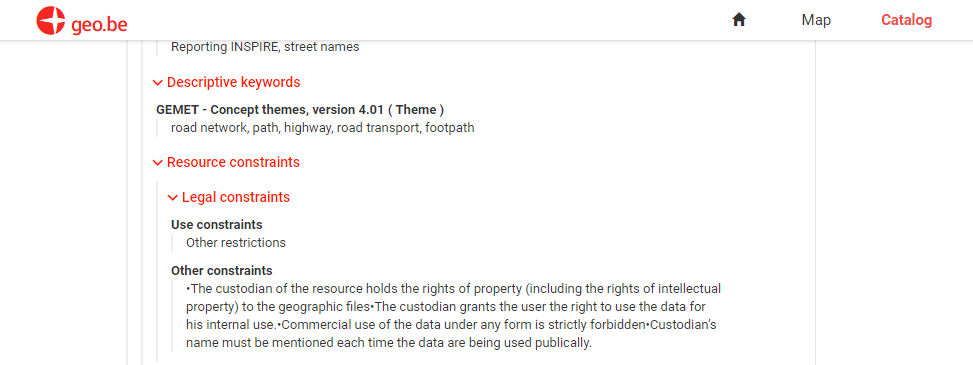

Licenses

- Licenses tell you what you can do with the content or data that you access.

- A license will tell you whether you can:

- republish the content or data on your own website

- derive new content or data from it

- make money by selling products that use it

- republish it while charging a fee for access

- Many licences will let you access content or data for free, but say that you cannot republish it or adapt it, or use it within commercial products. If you break the terms of the licence, the owner of the content or data can take you to court.

Open licenses

- The Open Definition differentiates between required and acceptable terms that may be included in licences applied to open works and datasets:

- Required terms are licensing permissions that must be present in order for a licence to be considered open.

- Acceptable terms are those which may be included in a licence, so long as they don’t otherwise conflict with the basic definitions of openness. These terms typically place restrictions on how data is reused by placing limitations on the forms of its reuse.

- The abilities to use and redistribute data are required provisions, while attribution and sharealike provisions are acceptable.

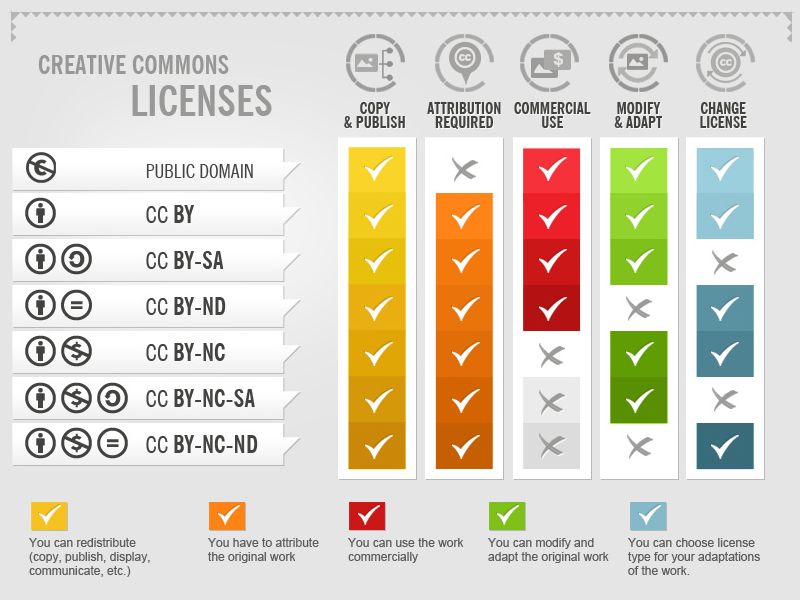

Standard licensing models

National: UK Open Government License (2010), Dutch GeoGedeeld framework, Datenlizenz Deutschland, Norwegian Licence for Open Government Data (NLOD), …

Thematic: SeaDataNet, OneGeology, ECOMET, etc.

INSPIRE licenses: basic and advanced

Transnational license frameworks:

- Creative Commons licenses

- Open Data Commons licenses

Examples

Examples

Examples

https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/licensing-types-examples/

Not all Creative Commons licenses are open licences

A public domain licence has no restrictions at all (technically, these indicate that you waive your rights to the content or data)

CC BY allows the user to redistribute, to create derivatives, such as a translation, and even use the publication for commercial activities, provided that appropriate credit is given to the author (BY) and that the user indicates whether the publication has been changed.

CC BY-SA is also an open license. The letters SA (share alike) indicate that the adjusted work should be shared under the same reuse rights, so with the same CC license.

NC (non-commercial use) and ND (no derivative works) are conditions that make the CC licenses more restrictive and thus are not really open.

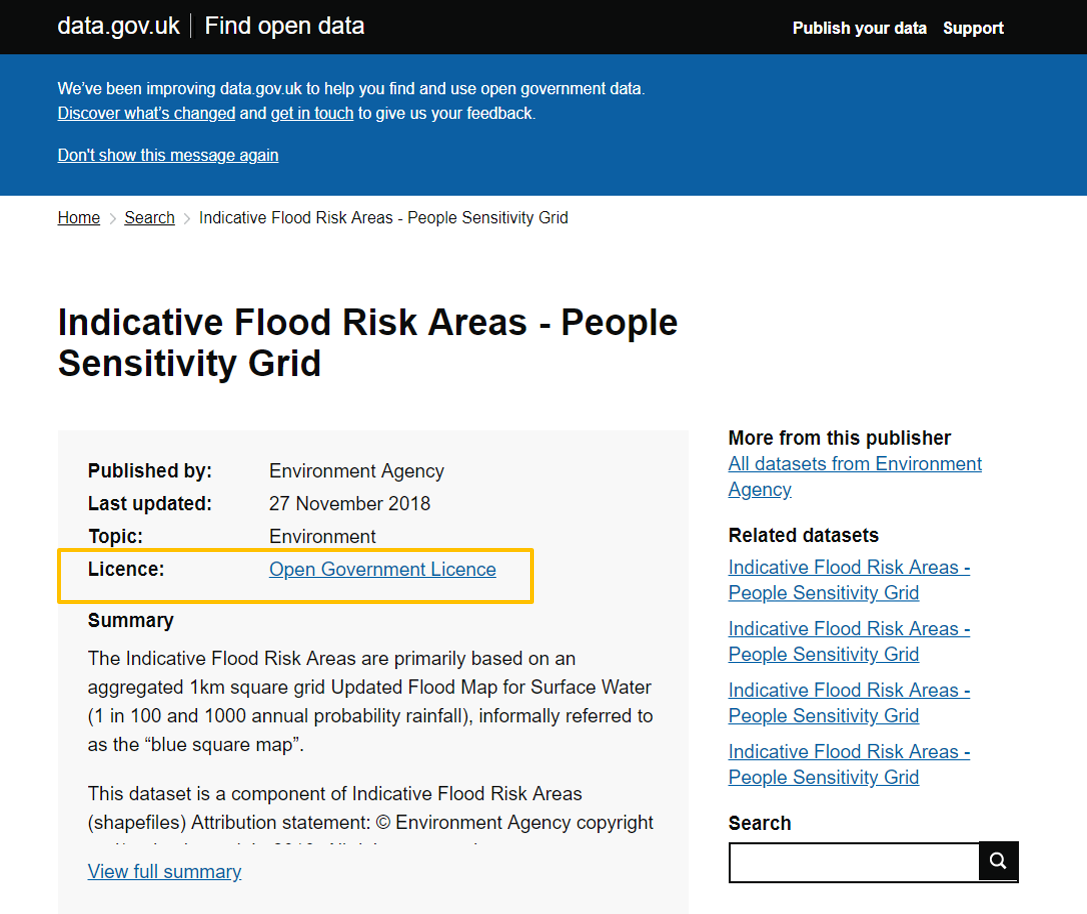

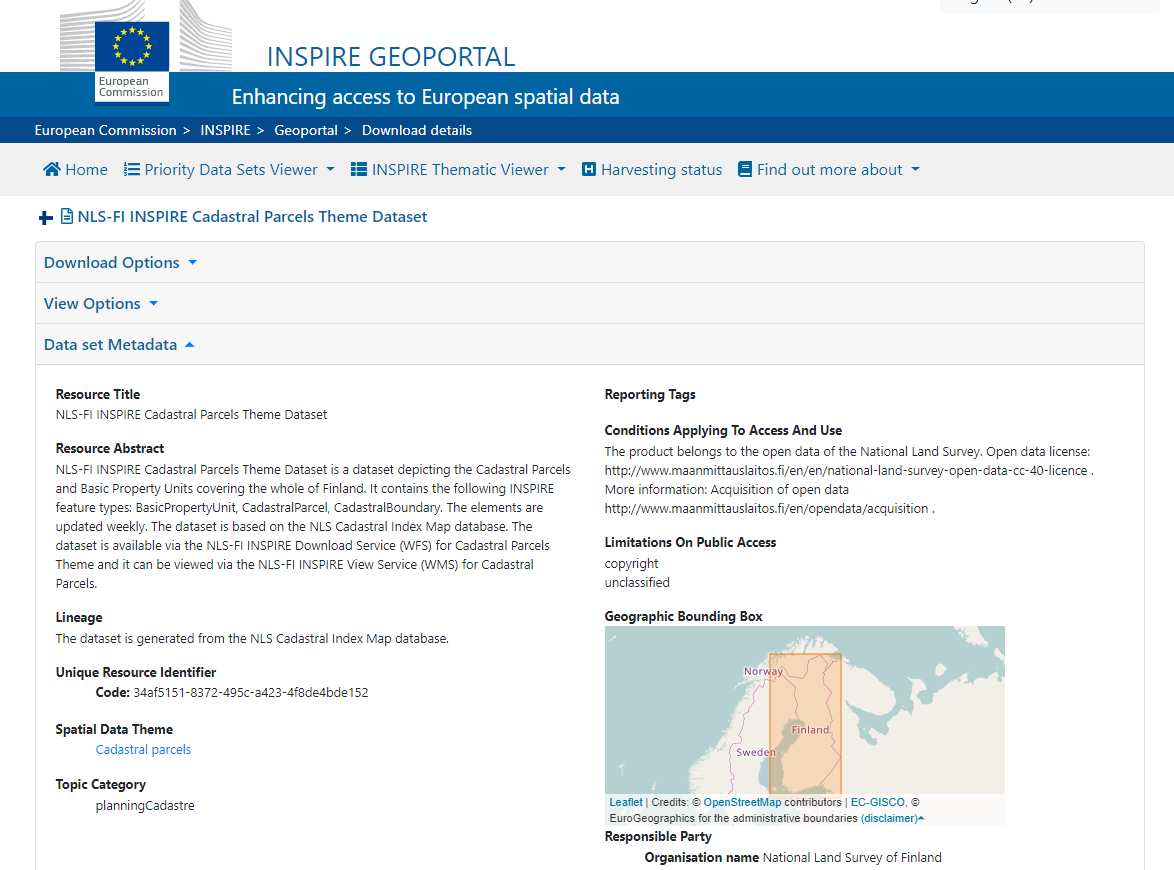

Indicate the license of data

The clearer you make it which licence applies to your content or data, the easier it is for reusers to know that they can reuse the content or data you are licensing.

Using both a human-readable description and computer-readable metadata:

- Human-readable descriptions and marks provided by Creative Commons (to be embedded within the content of the data)

- Also provide computer-readable metadata

SDI Data Policies

| 1 | Introduction |

| 2 | Legal framework on SDIs |

| 3 | Open data |

| 4 | Data sharing arrangements |

| 5 | Data ecosystems and data spaces |

Data ecosystems

- Data ecosystem can be defined as a complex socio-technical system of people, organisations, technology, policies and data in a specific area or domain that interact with one another and their surrounding environment to achieve a specific purpose.

- These ecosystems evolve and adapt through a cycle of data creation and sharing, data analytics, and value creation in the form of new products, services, or knowledge, which, when used, produce new data feeding back into the ecosystem.

- This cyclical process of data value adding and use, which in turn generates new data, distinguishes a data ecosystem from existing data infrastructures, which are characterised by a more linear process in which data is published and made discoverable and usable, but there is no feedback loop between users and providers.

Data spaces

- Already in 2018 the European Commission proposed “a package of measures as a key step towards a common data space in the EU - a seamless digital area with the scale that will enable the development of new products and services based on data”

- The 2020 European Strategy for Data also proposed the creation of “a single European data space –a genuine single market for data, open to data from across the world –where personal as well as non-personal data, including sensitive business data, are secure and businesses also have easy access to an almost infinite amount of high-quality industrial data, boosting growth and creating value, while minimising the human carbon and environmental footprint”

Data spaces

- The European Data Space should be a space where EU law can be enforced effectively, and where all data-driven products and services comply with the relevant norms of the EU’s single market.

- To this end, the EU should combine fit-for-purpose legislation and governance to ensure availability of data, with investments in standards, tools and infrastructures as well as competences for handling data. This favourable context, promoting incentives and choice, will lead to more data being stored and processed in the EU

- Data spaces should foster an ecosystem (of companies, civil society and individuals) creating new products and services based on more accessible data

Data spaces

- The European data space will give businesses in the EU the possibility to build on the scale of the Single market. Common 2European rules and efficient enforcement mechanisms should ensure that:

- data can flow within the EU and across sectors;

- European rules and values, in particular personal data protection, consumer protection legislation and competition law, are fully respected;

- the rules for access to and use of data are fair, practical and clear, and there are clear and trustworthy data governance mechanisms in place;

- there is an open, but assertive approach to international data flows, based on European values.

Key challenges

- Fragmentation between Member States is a major risk for the vision of a common European data space and for the further development of a genuine single market for data.

- A number of Member States have started with adaptations of their legal framework, such as on use of privately-held data by government authorities, data processing for scientific research purposes, or adaptations to competition law16.

- Others are only starting to explore how to handle the issues at stake.

- The emerging differences underline the importance of common action in order to leverage the scale of the internal market.

Key challenges

- Currently there is not enough data available for innovative re-use, including for the development of artificial intelligence.

- Challenges and issues can be grouped according to who is the data holder and who is the data user, but also depend on the nature of data involved (i.e. personal data, non-personal data, or mixed data-sets combining the two)

- Use of public sector information by business (government-to-business –G2B –data sharing)

- Sharing and use of privately-held data by other companies (business-to-business –B2B –data-sharing)

- Use of privately-held data by government authorities (business-to-government –B2G –data sharing)

- Sharing of data between public authorities

Reference list

- Craglia, M., & Masser, I. (1997). A European policy framework for geographic information. Computers, environment and urban systems, 21(6), 393-406.

- Granell, C., Gould, M., Manso, M. A., & Bernabe, M. A. (2009). Spatial data infrastructures. In Handbook of Research on Geoinformatics (pp. 36-41). IGI Global.

- Janssen, M., Charalabidis, Y., & Zuiderwijk, A. (2012). Benefits, adoption barriers and myths of open data and open government. Information systems management, 29(4), 258-268.

- Kitchin, R. (2014). The data revolution: Big data, open data, data infrastructures and their consequences. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

- Lauriault, T. P. (2018). Open spatial data. Understanding Spatial Media, R. Kitchin, TP Lauriault, and MW Wilson, Eds. SAGE Publications, London, 95-109.

- van Loenen, B., Vancauwenberghe, G., & Crompvoets, J. (Eds.). (2018). Open Data Exposed. Information Technology and Law Series (Vol. 30). T.M.C. Asser Press